gdb ouvre des files descriptor lorsqu'il est démarré.

Il devient donc très simple de détecter gdb depuis un binaire:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/gdb$ cat close3.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

cint main(void) {

if (close(3)==0) {

printf("Debugger detected, Bye\n");

exit(0);

}

printf("Je suis dans le main\n");

}

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/gdb$

et c'est tout:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/gdb$ gdb -n -q ./close3

Reading symbols from /home/mitsurugi/gdb/close3...done.

(gdb) r

Starting program: /home/mitsurugi/gdb/./close3

Debugger detected, Bye

[Inferior 1 (process 15890) exited normally]

(gdb) q

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/gdb$ ./close3

Je suis dans le main

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/gdb$

Simple et efficace.

Ca se contourne tout aussi facilement, il existe plein de doc sur le sujet.

Le problème avec cette méthode, c'est que n'importe quel reverser la voit immédiatement. On pourrait imaginer des crackmes plus fins avec une détection silencieuse du genre:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/gdb$ cat close3.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

char etat[32] = "gentil";

int main(void) {

if (close(3)==0) {

strcpy(etat,"mechant");

}

printf("Je suis dans le main\n");

printf("Je suis %s.\n", etat);

}

Ce qui donne:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/gdb$ ./close3

Je suis dans le main

Je suis gentil.

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/gdb$ gdb -n -q ./close3

Reading symbols from /home/mitsurugi/gdb/close3...done.

(gdb) r

Starting program: /home/mitsurugi/gdb/./close3

Je suis dans le main

Je suis mechant.

[Inferior 1 (process 16571) exited with code 021]

(gdb) q

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/gdb$

Cet exemple n'est pas très représentatif, mais on peut imaginer un changement de magic number, un appel à une fonction qui ne se fait pas ou ce genre de choses.

mardi 10 décembre 2013

jeudi 5 décembre 2013

linux anti debug trick

Sous linux, tous les outils de décompilation s'attendent à avoir des binaires bien formés.

Prenons l'exemple du binaire crackme.01.32 de crackmes.de. L'antidebug est simple à réaliser et très efficace comme nous allons voir: la partie section header du binaire est erronée. Un hexdump le montre bien:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ hexdump -C crackme.01.32 | head -4

00000000 7f 45 4c 46 01 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |.ELF............|

00000010 02 00 03 00 ff ff ff ff b0 84 04 08 34 00 00 00 |............4...|

00000020 ff ff ff ff 00 00 00 00 ff ff 20 00 08 00 ff ff |.......... .....|

00000030 ff ff ff ff 06 00 00 00 34 00 00 00 34 80 04 08 |........4...4...|

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

Les sections headers sont remplacées par des ff ff, voir le post précédent avec le grand tableau de l'elf101.

Et c'est suffisant pour mettre hors jeu les debuggers classiques sous linux que j'ai pu essayer:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ objdump -d crackme.01.32

objdump: crackme.01.32: File format not recognized

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ gdb -q crackme.01.32

"/home/mitsurugi/crackmes/crackme.01.32": not in executable format: Format de fichier non reconnu

(gdb) q

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ readelf -s crackme.01.32

readelf: Error: Unable to seek to 0xffffffff for section headers

readelf: Error: Unable to seek to 0xffffffff for section headers

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

Les debuggers spécialisés chargent le binaire, mais semblent avoir des problèmes par la suite. edb a crashé assez vite, radare2 charge le binaire, mais ne fait aucun mapping par la suite: tous octets du binaires sont simplement plaqué linéairement à partir de l'adresse 0x08048000. J'ai ouvert un bug chez radare2 du coup.

En fait, seul IDA semble bien s'en sortir. Le post de blog http://em386.blogspot.de/2006/10/elf-no-section-header-no-problem.html qui date de 2006 arrive exactement à la même conclusion.

Je trouve quand même ça fou que tous les debuggers s’appuient sur des sections qui ne sont pas utilisés à l'exécution. Cela signifie qu'il doit être possible de duper ces debuggers/reversers en forgeant des en-têtes de sections bien choisis. Comme le dit le post de blog plus haut, gdb est un peu dédié à l'analyse de code dont on a les sources, donc c'est normal qu'il ne soit pas robuste aux binaires mal fichus, mais c'est quand même dommage qu'il ne sache pas s'en sortir sans section headers.

J'ai envoyé une solution à crackmes.de en anglais en donnant une méthode sans IDA pour trouver la solution. Ca m'a permis de bien disséquer de l'ELF, mais c'est relativement long.

Solution:

Launch the binary to begin:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ ./crackme.01.32

Please tell me my password: password

No! No! No! No! Try again.

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ gdb -q ./crackme.01.32

"/home/mitsurugi/crackmes/./crackme.01.32": not in executable format: File format not recognized

gdb$ q

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

At a first glance we can see an antidebug trick by wiping the section header:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ readelf -s crackme.01.32

readelf: Error: Unable to seek to 0xffffffff for section headers

readelf: Error: Unable to seek to 0xffffffff for section headers

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

objdump fails at analyzing it, and gdb too. If we strings the binary we can also see:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ strings -n10 crackme.01.32

/lib/ld-linux.so.2

_IO_stdin_used

__libc_start_main

__gmon_start__

I'm sorry GDB! You are not allowed!

Tracing is not allowed... Bye

Please tell me my password:

The password is correct!

Congratulations!!!

No! No! No! No! Try again.

GCC: (GNU) 4.8.0

.note.ABI-tag

.note.gnu.build-id

.gnu.version

.gnu.version_r

.eh_frame_hdr

.init_array

.fini_array

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

The message about GDB let us assume that there are some other anti-gdb tricks, ptrace maybe:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ strings crackme.01.32 | grep ptrace

ptrace

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

So it's time to disass it.We know that section headers are not usefull at all when running a binary, but program header are mandatory. Let's see what we have:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ readelf -l crackme.01.32

readelf: Error: Unable to seek to 0xffffffff for section headers

readelf: Error: Unable to seek to 0xffffffff for section headers

Elf file type is EXEC (Executable file)

Entry point 0x80484b0

There are 8 program headers, starting at offset 52

Program Headers:

Type Offset VirtAddr PhysAddr FileSiz MemSiz Flg Align

PHDR 0x000034 0x08048034 0x08048034 0x00100 0x00100 R E 0x4

INTERP 0x000134 0x08048134 0x08048134 0x00013 0x00013 R 0x1

[Requesting program interpreter: /lib/ld-linux.so.2]

LOAD 0x000000 0x08048000 0x08048000 0x00a28 0x00a28 R E 0x1000

LOAD 0x000a28 0x08049a28 0x08049a28 0x00140 0x00180 RW 0x1000

DYNAMIC 0x000a38 0x08049a38 0x08049a38 0x000e8 0x000e8 RW 0x4

NOTE 0x000148 0x08048148 0x08048148 0x00044 0x00044 R 0x4

GNU_EH_FRAME 0x0008d4 0x080488d4 0x080488d4 0x00044 0x00044 R 0x4

GNU_STACK 0x000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000 0x00000 RW 0x4

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

So we can map some memory addresses with file offset.

First LOAD section:

From 0x08048000 to 0x08048a28, it's a linear mapping with the file from offset 0. But for bytes next, we have to make a gap of 0x1000.

Second LOAD section:

From 0x08049a28 to 0x08049a28+0x180 we have to map offset from files 0xa2 to 0xa28+0x140..

The DYNAMIC section, NOTE, GNU_EH_FRAME are not used for solving this crackme.

And now, with the help of ndisasm, we can solve the challenge by starting at entry point:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ ndisasm -au -o 0x08048000 -e 0x4b0 crackme.01.32 | head -14

08048000 31ED xor ebp,ebp

08048002 5E pop esi

08048003 89E1 mov ecx,esp

08048005 83E4F0 and esp,byte -0x10

08048008 50 push eax

08048009 54 push esp

0804800A 52 push edx

0804800B 6800880408 push dword 0x8048800

08048010 6890870408 push dword 0x8048790

08048015 51 push ecx

08048016 56 push esi

08048017 68C8860408 push dword 0x80486c8

0804801C E89FFFFFFF call dword 0x8047fc0

08048021 F4 hlt

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

This looks like pretty usual stuff. The 0x080486c8 should be the address of the main function.

Before tracing main, let's find some offset of some strings to help:

at 0x86a : Please tell me my password:

at 0x888 : The password is correct! Congratulations!!!

at 0x8b5 : No! No! No! No! Try again.

Now we try to find those references in the main function, because we know that somewhere, it should asks for a password, so we should see those addresses pushed on the stack and the function printf or puts called.

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ ndisasm -au -o 0x080486c8 -e 0x6c8 crackme.01.32 | head -41

080486C8 55 push ebp

080486C9 89E5 mov ebp,esp

080486CB 83E4F0 and esp,byte -0x10

080486CE 83EC20 sub esp,byte +0x20

080486D1 A1A09B0408 mov eax,[0x8049ba0]

080486D6 8944240C mov [esp+0xc],eax

080486DA C74424081C000000 mov dword [esp+0x8],0x1c

080486E2 C744240401000000 mov dword [esp+0x4],0x1

080486EA C704246A880408 mov dword [esp],0x804886a

address of "Please tell me my password"

080486F1 E83AFDFFFF call dword 0x8048430

It should be puts function

080486F6 A1809B0408 mov eax,[0x8049b80]

080486FB 89442408 mov [esp+0x8],eax

080486FF C744240407000000 mov dword [esp+0x4],0x7

08048707 8D442418 lea eax,[esp+0x18]

0804870B 890424 mov [esp],eax

0804870E E8FDFCFFFF call dword 0x8048410

08048713 8D442418 lea eax,[esp+0x18]

08048717 890424 mov [esp],eax

0804871A E823FFFFFF call dword 0x8048642

0804871F C7442404609B0408 mov dword [esp+0x4],0x8049b60

08048727 8D442418 lea eax,[esp+0x18]

0804872B 890424 mov [esp],eax

0804872E E842FFFFFF call dword 0x8048675

08048733 85C0 test eax,eax

08048735 7527 jnz 0x804875e

goes to loose func

08048737 A1A09B0408 mov eax,[0x8049ba0]

0804873C 8944240C mov [esp+0xc],eax

08048740 C74424082C000000 mov dword [esp+0x8],0x2c

08048748 C744240401000000 mov dword [esp+0x4],0x1

08048750 C7042488880408 mov dword [esp],0x8048888

address of winning string

08048757 E8D4FCFFFF call dword 0x8048430

puts function again

0804875C EB25 jmp short 0x8048783

0804875E A1A09B0408 mov eax,[0x8049ba0]

08048763 8944240C mov [esp+0xc],eax

08048767 C74424081B000000 mov dword [esp+0x8],0x1b

0804876F C744240401000000 mov dword [esp+0x4],0x1

08048777 C70424B5880408 mov dword [esp],0x80488b5

address of loose message

0804877E E8ADFCFFFF call dword 0x8048430

and puts function again

08048783 B800000000 mov eax,0x0

08048788 C9 leave

08048789 C3 ret

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

Things becomes clearer now. Everything important is here:

080486EA C704246A880408 mov dword [esp],0x804886a | Please tell me my password

080486F1 E83AFDFFFF call dword 0x8048430 | should be puts function

080486F6 A1809B0408 mov eax,[0x8049b80]

080486FB 89442408 mov [esp+0x8],eax

080486FF C744240407000000 mov dword [esp+0x4],0x7

08048707 8D442418 lea eax,[esp+0x18]

0804870B 890424 mov [esp],eax

0804870E E8FDFCFFFF call dword 0x8048410

A function is called, it would be logical that gets is called to retrieve the password entered by the user.

08048713 8D442418 lea eax,[esp+0x18]

08048717 890424 mov [esp],eax

0804871A E823FFFFFF call dword 0x8048642

Now it's interesting, what this function does? Password validation? Password transformation? Other?

0804871F C7442404609B0408 mov dword [esp+0x4],0x8049b60

Another point of interest. What we have at this address?

08048727 8D442418 lea eax,[esp+0x18]

0804872B 890424 mov [esp],eax

0804872E E842FFFFFF call dword 0x8048675

Another function? Validation of password?

08048733 85C0 test eax,eax

Makes sense: if validation function return something different than 0, go loose.

08048735 7527 jnz 0x804875e

Yep, it goes to loose function

So, we have to check addresses:

-0x08048410 : is it gets?

-0x08048642 : what happens there?

-0x08049b60 : what is there?

-0x08048675 : is it a validation function? How does it works?

Let's go:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ ndisasm -au -o 0x08048410 -e 0x410 crackme.01.32 | head -3

08048410 FF25309B0408 jmp dword [dword 0x8049b30]

08048416 6800000000 push dword 0x0

0804841B E9E0FFFFFF jmp dword 0x8048400

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

Ok, typically a GOT entry. I assume it's puts function.

next one

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ ndisasm -au -o 0x08048642 -e 0x642 crackme.01.32 | head -19

08048642 55 push ebp

08048643 89E5 mov ebp,esp

08048645 83EC10 sub esp,byte +0x10

08048648 C745FC00000000 mov dword [ebp-0x4],0x0

0804864F EB1C jmp short 0x804866d

08048651 8B55FC mov edx,[ebp-0x4]

08048654 8B4508 mov eax,[ebp+0x8]

08048657 01C2 add edx,eax

08048659 8B4DFC mov ecx,[ebp-0x4]

0804865C 8B4508 mov eax,[ebp+0x8]

0804865F 01C8 add eax,ecx

08048661 0FB600 movzx eax,byte [eax]

08048664 83F06C xor eax,byte +0x6c

Doing a simple XOR with value 0x6c

08048667 8802 mov [edx],al

08048669 8345FC01 add dword [ebp-0x4],byte +0x1

0804866D 837DFC05 cmp dword [ebp-0x4],byte +0x5

Looping 6 times.

08048671 7EDE jng 0x8048651

08048673 C9 leave

08048674 C3 ret

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

So this function just XOR with 0x6c the 6 first chars of the input.

Next one is 0x08049b60, we must take care of the address. It's 0x08049b60, so it's in the second load section. and the second load section is loaded with an offset of 0x0849000. It means that in the file, the 0x08049b60 are located at 0xb60. Let's see with hexdump what we have:

00000b60 1b 04 15 02 5c 18 00 00 47 43 43 3a 20 28 47 4e |....\...GCC: (GN|

00000b70 55 29 20 34 2e 38 2e 30 00 00 2e 73 68 73 74 72 |U) 4.8.0...shstr|6 bytes with a null at the end.

Now it's time for a big guess: the 0x08048675 is a simple validation function like strcmp.

If I resume how the binary works:

1/ It asks for a password

2/ It XORs the 6 first chars of the password with 0x6c

3/ It checks if the results is 0x1b 0x04 0x15 0X02 0x5c 0x18

(If it doesn't work, it means that we have to go deeper and disassemble 0x08048675 to learn what's going on there.)

We can easily calculate:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ cat sol.py

#! /usr/bin/python

v=''

for p in '\x1b\x04\x15\x02\x5c\x18':

v += chr((ord(p)^0x6c))

print v

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ ./sol.py

whyn0t

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

This results let think that all assumptions were rights, we can easily verify:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ ./crackme.01.32

Please tell me my password: whyn0t

The password is correct!

Congratulations!!!

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

Prenons l'exemple du binaire crackme.01.32 de crackmes.de. L'antidebug est simple à réaliser et très efficace comme nous allons voir: la partie section header du binaire est erronée. Un hexdump le montre bien:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ hexdump -C crackme.01.32 | head -4

00000000 7f 45 4c 46 01 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |.ELF............|

00000010 02 00 03 00 ff ff ff ff b0 84 04 08 34 00 00 00 |............4...|

00000020 ff ff ff ff 00 00 00 00 ff ff 20 00 08 00 ff ff |.......... .....|

00000030 ff ff ff ff 06 00 00 00 34 00 00 00 34 80 04 08 |........4...4...|

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

Les sections headers sont remplacées par des ff ff, voir le post précédent avec le grand tableau de l'elf101.

Et c'est suffisant pour mettre hors jeu les debuggers classiques sous linux que j'ai pu essayer:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ objdump -d crackme.01.32

objdump: crackme.01.32: File format not recognized

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ gdb -q crackme.01.32

"/home/mitsurugi/crackmes/crackme.01.32": not in executable format: Format de fichier non reconnu

(gdb) q

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ readelf -s crackme.01.32

readelf: Error: Unable to seek to 0xffffffff for section headers

readelf: Error: Unable to seek to 0xffffffff for section headers

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

Les debuggers spécialisés chargent le binaire, mais semblent avoir des problèmes par la suite. edb a crashé assez vite, radare2 charge le binaire, mais ne fait aucun mapping par la suite: tous octets du binaires sont simplement plaqué linéairement à partir de l'adresse 0x08048000. J'ai ouvert un bug chez radare2 du coup.

En fait, seul IDA semble bien s'en sortir. Le post de blog http://em386.blogspot.de/2006/10/elf-no-section-header-no-problem.html qui date de 2006 arrive exactement à la même conclusion.

Je trouve quand même ça fou que tous les debuggers s’appuient sur des sections qui ne sont pas utilisés à l'exécution. Cela signifie qu'il doit être possible de duper ces debuggers/reversers en forgeant des en-têtes de sections bien choisis. Comme le dit le post de blog plus haut, gdb est un peu dédié à l'analyse de code dont on a les sources, donc c'est normal qu'il ne soit pas robuste aux binaires mal fichus, mais c'est quand même dommage qu'il ne sache pas s'en sortir sans section headers.

J'ai envoyé une solution à crackmes.de en anglais en donnant une méthode sans IDA pour trouver la solution. Ca m'a permis de bien disséquer de l'ELF, mais c'est relativement long.

Mitsurugi

Solution:

Launch the binary to begin:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ ./crackme.01.32

Please tell me my password: password

No! No! No! No! Try again.

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ gdb -q ./crackme.01.32

"/home/mitsurugi/crackmes/./crackme.01.32": not in executable format: File format not recognized

gdb$ q

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

At a first glance we can see an antidebug trick by wiping the section header:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ readelf -s crackme.01.32

readelf: Error: Unable to seek to 0xffffffff for section headers

readelf: Error: Unable to seek to 0xffffffff for section headers

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

objdump fails at analyzing it, and gdb too. If we strings the binary we can also see:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ strings -n10 crackme.01.32

/lib/ld-linux.so.2

_IO_stdin_used

__libc_start_main

__gmon_start__

I'm sorry GDB! You are not allowed!

Tracing is not allowed... Bye

Please tell me my password:

The password is correct!

Congratulations!!!

No! No! No! No! Try again.

GCC: (GNU) 4.8.0

.note.ABI-tag

.note.gnu.build-id

.gnu.version

.gnu.version_r

.eh_frame_hdr

.init_array

.fini_array

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

The message about GDB let us assume that there are some other anti-gdb tricks, ptrace maybe:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ strings crackme.01.32 | grep ptrace

ptrace

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

So it's time to disass it.We know that section headers are not usefull at all when running a binary, but program header are mandatory. Let's see what we have:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ readelf -l crackme.01.32

readelf: Error: Unable to seek to 0xffffffff for section headers

readelf: Error: Unable to seek to 0xffffffff for section headers

Elf file type is EXEC (Executable file)

Entry point 0x80484b0

There are 8 program headers, starting at offset 52

Program Headers:

Type Offset VirtAddr PhysAddr FileSiz MemSiz Flg Align

PHDR 0x000034 0x08048034 0x08048034 0x00100 0x00100 R E 0x4

INTERP 0x000134 0x08048134 0x08048134 0x00013 0x00013 R 0x1

[Requesting program interpreter: /lib/ld-linux.so.2]

LOAD 0x000000 0x08048000 0x08048000 0x00a28 0x00a28 R E 0x1000

LOAD 0x000a28 0x08049a28 0x08049a28 0x00140 0x00180 RW 0x1000

DYNAMIC 0x000a38 0x08049a38 0x08049a38 0x000e8 0x000e8 RW 0x4

NOTE 0x000148 0x08048148 0x08048148 0x00044 0x00044 R 0x4

GNU_EH_FRAME 0x0008d4 0x080488d4 0x080488d4 0x00044 0x00044 R 0x4

GNU_STACK 0x000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000 0x00000 RW 0x4

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

So we can map some memory addresses with file offset.

First LOAD section:

From 0x08048000 to 0x08048a28, it's a linear mapping with the file from offset 0. But for bytes next, we have to make a gap of 0x1000.

Second LOAD section:

From 0x08049a28 to 0x08049a28+0x180 we have to map offset from files 0xa2 to 0xa28+0x140..

The DYNAMIC section, NOTE, GNU_EH_FRAME are not used for solving this crackme.

And now, with the help of ndisasm, we can solve the challenge by starting at entry point:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ ndisasm -au -o 0x08048000 -e 0x4b0 crackme.01.32 | head -14

08048000 31ED xor ebp,ebp

08048002 5E pop esi

08048003 89E1 mov ecx,esp

08048005 83E4F0 and esp,byte -0x10

08048008 50 push eax

08048009 54 push esp

0804800A 52 push edx

0804800B 6800880408 push dword 0x8048800

08048010 6890870408 push dword 0x8048790

08048015 51 push ecx

08048016 56 push esi

08048017 68C8860408 push dword 0x80486c8

0804801C E89FFFFFFF call dword 0x8047fc0

08048021 F4 hlt

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

This looks like pretty usual stuff. The 0x080486c8 should be the address of the main function.

Before tracing main, let's find some offset of some strings to help:

at 0x86a : Please tell me my password:

at 0x888 : The password is correct! Congratulations!!!

at 0x8b5 : No! No! No! No! Try again.

Now we try to find those references in the main function, because we know that somewhere, it should asks for a password, so we should see those addresses pushed on the stack and the function printf or puts called.

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ ndisasm -au -o 0x080486c8 -e 0x6c8 crackme.01.32 | head -41

080486C8 55 push ebp

080486C9 89E5 mov ebp,esp

080486CB 83E4F0 and esp,byte -0x10

080486CE 83EC20 sub esp,byte +0x20

080486D1 A1A09B0408 mov eax,[0x8049ba0]

080486D6 8944240C mov [esp+0xc],eax

080486DA C74424081C000000 mov dword [esp+0x8],0x1c

080486E2 C744240401000000 mov dword [esp+0x4],0x1

080486EA C704246A880408 mov dword [esp],0x804886a

address of "Please tell me my password"

080486F1 E83AFDFFFF call dword 0x8048430

It should be puts function

080486F6 A1809B0408 mov eax,[0x8049b80]

080486FB 89442408 mov [esp+0x8],eax

080486FF C744240407000000 mov dword [esp+0x4],0x7

08048707 8D442418 lea eax,[esp+0x18]

0804870B 890424 mov [esp],eax

0804870E E8FDFCFFFF call dword 0x8048410

08048713 8D442418 lea eax,[esp+0x18]

08048717 890424 mov [esp],eax

0804871A E823FFFFFF call dword 0x8048642

0804871F C7442404609B0408 mov dword [esp+0x4],0x8049b60

08048727 8D442418 lea eax,[esp+0x18]

0804872B 890424 mov [esp],eax

0804872E E842FFFFFF call dword 0x8048675

08048733 85C0 test eax,eax

08048735 7527 jnz 0x804875e

goes to loose func

08048737 A1A09B0408 mov eax,[0x8049ba0]

0804873C 8944240C mov [esp+0xc],eax

08048740 C74424082C000000 mov dword [esp+0x8],0x2c

08048748 C744240401000000 mov dword [esp+0x4],0x1

08048750 C7042488880408 mov dword [esp],0x8048888

address of winning string

08048757 E8D4FCFFFF call dword 0x8048430

puts function again

0804875C EB25 jmp short 0x8048783

0804875E A1A09B0408 mov eax,[0x8049ba0]

08048763 8944240C mov [esp+0xc],eax

08048767 C74424081B000000 mov dword [esp+0x8],0x1b

0804876F C744240401000000 mov dword [esp+0x4],0x1

08048777 C70424B5880408 mov dword [esp],0x80488b5

address of loose message

0804877E E8ADFCFFFF call dword 0x8048430

and puts function again

08048783 B800000000 mov eax,0x0

08048788 C9 leave

08048789 C3 ret

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

Things becomes clearer now. Everything important is here:

080486EA C704246A880408 mov dword [esp],0x804886a | Please tell me my password

080486F1 E83AFDFFFF call dword 0x8048430 | should be puts function

080486F6 A1809B0408 mov eax,[0x8049b80]

080486FB 89442408 mov [esp+0x8],eax

080486FF C744240407000000 mov dword [esp+0x4],0x7

08048707 8D442418 lea eax,[esp+0x18]

0804870B 890424 mov [esp],eax

0804870E E8FDFCFFFF call dword 0x8048410

A function is called, it would be logical that gets is called to retrieve the password entered by the user.

08048713 8D442418 lea eax,[esp+0x18]

08048717 890424 mov [esp],eax

0804871A E823FFFFFF call dword 0x8048642

Now it's interesting, what this function does? Password validation? Password transformation? Other?

0804871F C7442404609B0408 mov dword [esp+0x4],0x8049b60

Another point of interest. What we have at this address?

08048727 8D442418 lea eax,[esp+0x18]

0804872B 890424 mov [esp],eax

0804872E E842FFFFFF call dword 0x8048675

Another function? Validation of password?

08048733 85C0 test eax,eax

Makes sense: if validation function return something different than 0, go loose.

08048735 7527 jnz 0x804875e

Yep, it goes to loose function

So, we have to check addresses:

-0x08048410 : is it gets?

-0x08048642 : what happens there?

-0x08049b60 : what is there?

-0x08048675 : is it a validation function? How does it works?

Let's go:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ ndisasm -au -o 0x08048410 -e 0x410 crackme.01.32 | head -3

08048410 FF25309B0408 jmp dword [dword 0x8049b30]

08048416 6800000000 push dword 0x0

0804841B E9E0FFFFFF jmp dword 0x8048400

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

Ok, typically a GOT entry. I assume it's puts function.

next one

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ ndisasm -au -o 0x08048642 -e 0x642 crackme.01.32 | head -19

08048642 55 push ebp

08048643 89E5 mov ebp,esp

08048645 83EC10 sub esp,byte +0x10

08048648 C745FC00000000 mov dword [ebp-0x4],0x0

0804864F EB1C jmp short 0x804866d

08048651 8B55FC mov edx,[ebp-0x4]

08048654 8B4508 mov eax,[ebp+0x8]

08048657 01C2 add edx,eax

08048659 8B4DFC mov ecx,[ebp-0x4]

0804865C 8B4508 mov eax,[ebp+0x8]

0804865F 01C8 add eax,ecx

08048661 0FB600 movzx eax,byte [eax]

08048664 83F06C xor eax,byte +0x6c

Doing a simple XOR with value 0x6c

08048667 8802 mov [edx],al

08048669 8345FC01 add dword [ebp-0x4],byte +0x1

0804866D 837DFC05 cmp dword [ebp-0x4],byte +0x5

Looping 6 times.

08048671 7EDE jng 0x8048651

08048673 C9 leave

08048674 C3 ret

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

So this function just XOR with 0x6c the 6 first chars of the input.

Next one is 0x08049b60, we must take care of the address. It's 0x08049b60, so it's in the second load section. and the second load section is loaded with an offset of 0x0849000. It means that in the file, the 0x08049b60 are located at 0xb60. Let's see with hexdump what we have:

00000b60 1b 04 15 02 5c 18 00 00 47 43 43 3a 20 28 47 4e |....\...GCC: (GN|

00000b70 55 29 20 34 2e 38 2e 30 00 00 2e 73 68 73 74 72 |U) 4.8.0...shstr|6 bytes with a null at the end.

Now it's time for a big guess: the 0x08048675 is a simple validation function like strcmp.

If I resume how the binary works:

1/ It asks for a password

2/ It XORs the 6 first chars of the password with 0x6c

3/ It checks if the results is 0x1b 0x04 0x15 0X02 0x5c 0x18

(If it doesn't work, it means that we have to go deeper and disassemble 0x08048675 to learn what's going on there.)

We can easily calculate:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ cat sol.py

#! /usr/bin/python

v=''

for p in '\x1b\x04\x15\x02\x5c\x18':

v += chr((ord(p)^0x6c))

print v

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ ./sol.py

whyn0t

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

This results let think that all assumptions were rights, we can easily verify:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$ ./crackme.01.32

Please tell me my password: whyn0t

The password is correct!

Congratulations!!!

mitsurugi@mitsu:~/crackmes$

mercredi 20 novembre 2013

Autopsie d'un fichier ELF

La réponse à toute les questions qu'on se pose sur les fichiers ELF se trouve ici:

https://code.google.com/p/corkami/wiki/ELF101

Très clair.

https://code.google.com/p/corkami/wiki/ELF101

Très clair.

Mitsurugi

lundi 11 novembre 2013

un crackme

Je surfe pas mal sur crackmes.de en ce moment. J'en ai vu un intéressant. Il s'agit de synamics's Xrockm.

Méthode de résolution; tout d'abord, on essaye les classiques:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ ./crackme_x86

What is the password?

password

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ strace -e trace=open ./crackme_x86

open("/etc/ld.so.cache", O_RDONLY) = 3

open("/lib/libc.so.6", O_RDONLY) = 3

--- SIGCHLD (Child exited) @ 0 (0) ---

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ gdb -q ./crackme_x86

Reading symbols from /home/mitsurugi/crackme_x86...(no debugging symbols found)...done.

(gdb) r

Starting program: /home/mitsurugi/crackme_x86

^C

^Z

Processus arrêté

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$

Ok, on a un programme qui demande un mot de passe, qui n'est pas traçable avec strace, et qui semble planter gdb. Il faut regarder de plus près:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ strings crackme_x86

(...)

srand

puts

time

stdin

fgets

malloc

system

ptrace

__libc_start_main

(...)

You WIN, congratulations...

killall -q gdb

killall -q strace

Sem cheat, fedepe...

What is the password?

(...)

Ok, donc l'anti debug vu plus haut est seulement un killall. Et ça, sous linux, ça se contourne en 3s:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ cp /usr/bin/strace STRACE

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ cp /usr/bin/gdb GDB

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$

et voilà. Plus d'antidebug. Ceci dit, strace ne nous apprend pas grand chose:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ ./STRACE ./crackme_x86

execve("./crackme_x86", ["./crackme_x86"], [/* 27 vars */]) = 0

brk(0) = 0x804b000

(...)

write(1, "What is the password?\n", 22What is the password?

) = 22

fstat64(0, {st_mode=S_IFCHR|0620, st_rdev=makedev(136, 2), ...}) = 0

mmap2(NULL, 4096, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0xb77d6000

read(0, password

"password\n", 1024) = 9

exit_group(0) = ?

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$

Bon, c'est curieux, on donne le mot de passe, et bam, exit (???) sans autre opération. Il est temps de lancer gdb.

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ ./GDB -q ./crackme_x86

Reading symbols from /home/mitsurugi/crackme_x86...(no debugging symbols found)...done.

(gdb) r

Starting program: /home/mitsurugi/crackme_x86

Sem cheat, fedepe...

What is the password?

^Z

Program received signal SIGTSTP, Stopped (user).

0xb7f36dde in __read_nocancel () from /lib/libc.so.6

0xb7f36dde, mmmh, on est pas dans le main. Voyons voir ou nous sommes, et quelles sont les instructions qui vont suivre:

(gdb) bt

#0 0xb7f36dde in __read_nocancel () from /lib/libc.so.6

#1 0xb7ed81a3 in _IO_new_file_underflow () from /lib/libc.so.6

#2 0xb7ed938b in _IO_default_uflow_internal () from /lib/libc.so.6

#3 0xb7ed917a in __uflow () from /lib/libc.so.6

#4 0xb7eccac4 in _IO_getline_info_internal () from /lib/libc.so.6

#5 0xb7ecca11 in _IO_getline_internal () from /lib/libc.so.6

#6 0xb7ecb91a in fgets () from /lib/libc.so.6

#7 0x080487c5 in main ()

(gdb) x/10i 0x080487c5

0x80487c5 <main+424>: movzbl 0x804a040,%eax

0x80487cc <main+431>: cmp $0x6f,%al

0x80487ce <main+433>: je 0x80487d7 <main+442>

0x80487d0 <main+435>: movb $0x61,0x804a03d

0x80487d7 <main+442>: mov $0x0,%eax

0x80487dc <main+447>: leave

0x80487dd <main+448>: ret

0x80487de: nop

0x80487df: nop

0x80487e0 <__libc_csu_init>: push %ebp

(gdb)

Ok, donc juste après le fgets, on fait un movzbl d'une adresse puis on compare si l'octet (AL) vaut 'o' (\x6F). On break ici, et on regarde ce qu'on a à cette adresse:

(gdb) b * 0x80487cc

Breakpoint 1 at 0x80487cc

(gdb) c

Continuing.

Program received signal SIGTSTP, Stopped (user).

0xb7f36dde in __read_nocancel () from /lib/libc.so.6

(gdb) c

Continuing.

password

Breakpoint 1, 0x080487cc in main ()

(gdb) x/s 0x804a040

0x804a040 <password+4>: "wor"

(gdb)

Ok, on est à password+4, ce qui est une information très intéressante. Le movzbl ne prend qu'un seul octet et met le reste à zéro. Ce qui revient à dire que le 5e octet du mot de passe vaut 'o'. Là, j'ai 'w' donc ça va échouer. Pas de problèmes pour éviter cela:

(gdb) set $eax=0x6f

Et on continue:

(gdb) x/10i $eip

=> 0x80487cc <main+431>: cmp $0x6f,%al

0x80487ce <main+433>: je 0x80487d7 <main+442>

0x80487d0 <main+435>: movb $0x61,0x804a03d

0x80487d7 <main+442>: mov $0x0,%eax

0x80487dc <main+447>: leave

0x80487dd <main+448>: ret

0x80487de: nop

0x80487df: nop

0x80487e0 <__libc_csu_init>: push %ebp

0x80487e1 <__libc_csu_init+1>: push %edi

(gdb) nexti

0x080487ce in main ()

(gdb) nexti

0x080487d7 in main ()

(gdb) nexti

0x080487dc in main ()

(gdb) nexti

0x080487dd in main ()

(gdb) nexti

0xb7e82db6 in __libc_start_main () from /lib/libc.so.6

(gdb) nexti

0xb7e82db9 in __libc_start_main () from /lib/libc.so.6

(gdb) nexti

Program exited normally.

Et là, je suis ennuyé car le programme "exit normally" (??).

Il y a donc manifestement quelquechose qui se passe avant ou après l'entrée du mot passe qui vérifie quelque chose. Cela rejoint le strace qui exite directement après l'entrée du mot de passe. Là, j'ai regardé les fonctions avec objdump pour me donner une idée:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ objdump -d crackme_x86 | grep ">:"

080483b0 <_init>:

080483e0 <fgets@plt-0x10>:

080483f0 <fgets@plt>:

08048400 <time@plt>:

08048410 <malloc@plt>:

08048420 <puts@plt>:

08048430 <system@plt>:

08048440 <__gmon_start__@plt>:

08048450 <srand@plt>:

08048460 <__libc_start_main@plt>:

08048470 <rand@plt>:

08048480 <ptrace@plt>:

08048490 <_start>:

080484c0 <__do_global_dtors_aux>:

08048520 <frame_dummy>:

08048544 <_finit_>:

08048584 <_init_>:

0804861d <main>:

080487e0 <__libc_csu_init>:

08048850 <__libc_csu_fini>:

08048852 <__i686.get_pc_thunk.bx>:

08048860 <__do_global_ctors_aux>:

0804888c <_fini>:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$

Il y a une fonction qui a un nom qui m'étonne: _finit_. Allons breaker sur elle et voir quand elle est appelée:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ ./GDB -q ./crackme_x86

Reading symbols from /home/mitsurugi/crackme_x86...(no debugging symbols found)...done.

(gdb) b * _finit_

Breakpoint 1 at 0x8048544

(gdb) r

Starting program: /home/mitsurugi/crackme_x86

Sem cheat, fedepe...

What is the password?

ooooo

Breakpoint 1, 0x08048544 in _finit_ ()

(gdb)

Ok, ça c'est intéressant, elle est bien appelée après avoir entré le mot de passe.

(gdb) bt

#0 0x08048544 in _finit_ ()

#1 0xb7ff0674 in _dl_fini () from /lib/ld-linux.so.2

#2 0xb7e9bc5f in exit () from /lib/libc.so.6

#3 0xb7e82dbe in __libc_start_main () from /lib/libc.so.6

#4 0x080484b1 in _start ()

Et elle est bien appelée depuis exit(). Et la fonction est très simple à lire:

(gdb) x/19i $eip

=> 0x8048544 <_finit_>: push %ebp

0x8048545 <_finit_+1>: mov %esp,%ebp

0x8048547 <_finit_+3>: sub $0x18,%esp

0x804854a <_finit_+6>: movzbl 0x804a03c,%eax

0x8048551 <_finit_+13>: cmp $0x68,%al

0x8048553 <_finit_+15>: jne 0x8048582 <_finit_+62>

0x8048555 <_finit_+17>: movzbl 0x804a03d,%eax

0x804855c <_finit_+24>: cmp $0x65,%al

0x804855e <_finit_+26>: jne 0x8048582 <_finit_+62>

0x8048560 <_finit_+28>: movzbl 0x804a03e,%eax

0x8048567 <_finit_+35>: cmp $0x6c,%al

0x8048569 <_finit_+37>: jne 0x8048582 <_finit_+62>

0x804856b <_finit_+39>: movzbl 0x804a03f,%eax

0x8048572 <_finit_+46>: cmp $0x6c,%al

0x8048574 <_finit_+48>: jne 0x8048582 <_finit_+62>

0x8048576 <_finit_+50>: movl $0x80488b0,(%esp)

0x804857d <_finit_+57>: call 0x8048420 <puts@plt>

0x8048582 <_finit_+62>: leave

0x8048583 <_finit_+63>: ret

(gdb)

La fonction va donc lire à 0x804a03c (password), puis à

0x804a03d (password+1) etc.. si l'octet vaut \x68, puis \x65, \x6c et \x6c, soit:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ printf '\x68\x65\x6c\x6c\n'

hell

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$

Ok. Le 5e caractère doit être un 'o', les 4 premiers valent 'hell', la solution est donc tout mot commençant par 'hello' :

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ ./crackme_x86

What is the password?

hello

You WIN, congratulations...

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ ./crackme_x86

What is the password?

hellocoton

You WIN, congratulations...

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$

La chose que je ne m'explique pas, c'est comment la fonction _finit_ fait pour être appelée, alors qu'on ne la voit nulle part.

Méthode de résolution; tout d'abord, on essaye les classiques:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ ./crackme_x86

What is the password?

password

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ strace -e trace=open ./crackme_x86

open("/etc/ld.so.cache", O_RDONLY) = 3

open("/lib/libc.so.6", O_RDONLY) = 3

--- SIGCHLD (Child exited) @ 0 (0) ---

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ gdb -q ./crackme_x86

Reading symbols from /home/mitsurugi/crackme_x86...(no debugging symbols found)...done.

(gdb) r

Starting program: /home/mitsurugi/crackme_x86

^C

^Z

Processus arrêté

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$

Ok, on a un programme qui demande un mot de passe, qui n'est pas traçable avec strace, et qui semble planter gdb. Il faut regarder de plus près:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ strings crackme_x86

(...)

srand

puts

time

stdin

fgets

malloc

system

ptrace

__libc_start_main

(...)

You WIN, congratulations...

killall -q gdb

killall -q strace

Sem cheat, fedepe...

What is the password?

(...)

Ok, donc l'anti debug vu plus haut est seulement un killall. Et ça, sous linux, ça se contourne en 3s:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ cp /usr/bin/strace STRACE

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ cp /usr/bin/gdb GDB

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$

et voilà. Plus d'antidebug. Ceci dit, strace ne nous apprend pas grand chose:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ ./STRACE ./crackme_x86

execve("./crackme_x86", ["./crackme_x86"], [/* 27 vars */]) = 0

brk(0) = 0x804b000

(...)

write(1, "What is the password?\n", 22What is the password?

) = 22

fstat64(0, {st_mode=S_IFCHR|0620, st_rdev=makedev(136, 2), ...}) = 0

mmap2(NULL, 4096, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0xb77d6000

read(0, password

"password\n", 1024) = 9

exit_group(0) = ?

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$

Bon, c'est curieux, on donne le mot de passe, et bam, exit (???) sans autre opération. Il est temps de lancer gdb.

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ ./GDB -q ./crackme_x86

Reading symbols from /home/mitsurugi/crackme_x86...(no debugging symbols found)...done.

(gdb) r

Starting program: /home/mitsurugi/crackme_x86

Sem cheat, fedepe...

What is the password?

^Z

Program received signal SIGTSTP, Stopped (user).

0xb7f36dde in __read_nocancel () from /lib/libc.so.6

0xb7f36dde, mmmh, on est pas dans le main. Voyons voir ou nous sommes, et quelles sont les instructions qui vont suivre:

(gdb) bt

#0 0xb7f36dde in __read_nocancel () from /lib/libc.so.6

#1 0xb7ed81a3 in _IO_new_file_underflow () from /lib/libc.so.6

#2 0xb7ed938b in _IO_default_uflow_internal () from /lib/libc.so.6

#3 0xb7ed917a in __uflow () from /lib/libc.so.6

#4 0xb7eccac4 in _IO_getline_info_internal () from /lib/libc.so.6

#5 0xb7ecca11 in _IO_getline_internal () from /lib/libc.so.6

#6 0xb7ecb91a in fgets () from /lib/libc.so.6

#7 0x080487c5 in main ()

(gdb) x/10i 0x080487c5

0x80487c5 <main+424>: movzbl 0x804a040,%eax

0x80487cc <main+431>: cmp $0x6f,%al

0x80487ce <main+433>: je 0x80487d7 <main+442>

0x80487d0 <main+435>: movb $0x61,0x804a03d

0x80487d7 <main+442>: mov $0x0,%eax

0x80487dc <main+447>: leave

0x80487dd <main+448>: ret

0x80487de: nop

0x80487df: nop

0x80487e0 <__libc_csu_init>: push %ebp

(gdb)

Ok, donc juste après le fgets, on fait un movzbl d'une adresse puis on compare si l'octet (AL) vaut 'o' (\x6F). On break ici, et on regarde ce qu'on a à cette adresse:

(gdb) b * 0x80487cc

Breakpoint 1 at 0x80487cc

(gdb) c

Continuing.

Program received signal SIGTSTP, Stopped (user).

0xb7f36dde in __read_nocancel () from /lib/libc.so.6

(gdb) c

Continuing.

password

Breakpoint 1, 0x080487cc in main ()

(gdb) x/s 0x804a040

0x804a040 <password+4>: "wor"

(gdb)

Ok, on est à password+4, ce qui est une information très intéressante. Le movzbl ne prend qu'un seul octet et met le reste à zéro. Ce qui revient à dire que le 5e octet du mot de passe vaut 'o'. Là, j'ai 'w' donc ça va échouer. Pas de problèmes pour éviter cela:

(gdb) set $eax=0x6f

Et on continue:

(gdb) x/10i $eip

=> 0x80487cc <main+431>: cmp $0x6f,%al

0x80487ce <main+433>: je 0x80487d7 <main+442>

0x80487d0 <main+435>: movb $0x61,0x804a03d

0x80487d7 <main+442>: mov $0x0,%eax

0x80487dc <main+447>: leave

0x80487dd <main+448>: ret

0x80487de: nop

0x80487df: nop

0x80487e0 <__libc_csu_init>: push %ebp

0x80487e1 <__libc_csu_init+1>: push %edi

(gdb) nexti

0x080487ce in main ()

(gdb) nexti

0x080487d7 in main ()

(gdb) nexti

0x080487dc in main ()

(gdb) nexti

0x080487dd in main ()

(gdb) nexti

0xb7e82db6 in __libc_start_main () from /lib/libc.so.6

(gdb) nexti

0xb7e82db9 in __libc_start_main () from /lib/libc.so.6

(gdb) nexti

Program exited normally.

Et là, je suis ennuyé car le programme "exit normally" (??).

Il y a donc manifestement quelquechose qui se passe avant ou après l'entrée du mot passe qui vérifie quelque chose. Cela rejoint le strace qui exite directement après l'entrée du mot de passe. Là, j'ai regardé les fonctions avec objdump pour me donner une idée:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ objdump -d crackme_x86 | grep ">:"

080483b0 <_init>:

080483e0 <fgets@plt-0x10>:

080483f0 <fgets@plt>:

08048400 <time@plt>:

08048410 <malloc@plt>:

08048420 <puts@plt>:

08048430 <system@plt>:

08048440 <__gmon_start__@plt>:

08048450 <srand@plt>:

08048460 <__libc_start_main@plt>:

08048470 <rand@plt>:

08048480 <ptrace@plt>:

08048490 <_start>:

080484c0 <__do_global_dtors_aux>:

08048520 <frame_dummy>:

08048544 <_finit_>:

08048584 <_init_>:

0804861d <main>:

080487e0 <__libc_csu_init>:

08048850 <__libc_csu_fini>:

08048852 <__i686.get_pc_thunk.bx>:

08048860 <__do_global_ctors_aux>:

0804888c <_fini>:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$

Il y a une fonction qui a un nom qui m'étonne: _finit_. Allons breaker sur elle et voir quand elle est appelée:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ ./GDB -q ./crackme_x86

Reading symbols from /home/mitsurugi/crackme_x86...(no debugging symbols found)...done.

(gdb) b * _finit_

Breakpoint 1 at 0x8048544

(gdb) r

Starting program: /home/mitsurugi/crackme_x86

Sem cheat, fedepe...

What is the password?

ooooo

Breakpoint 1, 0x08048544 in _finit_ ()

(gdb)

Ok, ça c'est intéressant, elle est bien appelée après avoir entré le mot de passe.

(gdb) bt

#0 0x08048544 in _finit_ ()

#1 0xb7ff0674 in _dl_fini () from /lib/ld-linux.so.2

#2 0xb7e9bc5f in exit () from /lib/libc.so.6

#3 0xb7e82dbe in __libc_start_main () from /lib/libc.so.6

#4 0x080484b1 in _start ()

Et elle est bien appelée depuis exit(). Et la fonction est très simple à lire:

(gdb) x/19i $eip

=> 0x8048544 <_finit_>: push %ebp

0x8048545 <_finit_+1>: mov %esp,%ebp

0x8048547 <_finit_+3>: sub $0x18,%esp

0x804854a <_finit_+6>: movzbl 0x804a03c,%eax

0x8048551 <_finit_+13>: cmp $0x68,%al

0x8048553 <_finit_+15>: jne 0x8048582 <_finit_+62>

0x8048555 <_finit_+17>: movzbl 0x804a03d,%eax

0x804855c <_finit_+24>: cmp $0x65,%al

0x804855e <_finit_+26>: jne 0x8048582 <_finit_+62>

0x8048560 <_finit_+28>: movzbl 0x804a03e,%eax

0x8048567 <_finit_+35>: cmp $0x6c,%al

0x8048569 <_finit_+37>: jne 0x8048582 <_finit_+62>

0x804856b <_finit_+39>: movzbl 0x804a03f,%eax

0x8048572 <_finit_+46>: cmp $0x6c,%al

0x8048574 <_finit_+48>: jne 0x8048582 <_finit_+62>

0x8048576 <_finit_+50>: movl $0x80488b0,(%esp)

0x804857d <_finit_+57>: call 0x8048420 <puts@plt>

0x8048582 <_finit_+62>: leave

0x8048583 <_finit_+63>: ret

(gdb)

La fonction va donc lire à 0x804a03c (password), puis à

0x804a03d (password+1) etc.. si l'octet vaut \x68, puis \x65, \x6c et \x6c, soit:

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ printf '\x68\x65\x6c\x6c\n'

hell

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$

Ok. Le 5e caractère doit être un 'o', les 4 premiers valent 'hell', la solution est donc tout mot commençant par 'hello' :

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ ./crackme_x86

What is the password?

hello

You WIN, congratulations...

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$ ./crackme_x86

What is the password?

hellocoton

You WIN, congratulations...

mitsurugi@mitsu:~$

La chose que je ne m'explique pas, c'est comment la fonction _finit_ fait pour être appelée, alors qu'on ne la voit nulle part.

Mitsurugi

lundi 4 novembre 2013

badbios plus puissant que stuxnet?

Si vous lisez un peu l'actualité, vous n'avez pas pu passer à côté.

Un chercher (Dragos Ruiu) a trouvé un nouveau virus qui fait froid dans le dos:

Vous n'y croyez pas?

https://twitter.com/dragosr

http://arstechnica.com/security/2013/10/meet-badbios-the-mysterious-mac-and-pc-malware-that-jumps-airgaps/

http://www.rootwyrm.com/2013/11/the-badbios-analysis-is-wrong/

http://blog.sesse.net/blog/tech/2013-11-02-13-25_badbios_and_ultrasound.html

Un chercher (Dragos Ruiu) a trouvé un nouveau virus qui fait froid dans le dos:

- vous utilisez openBSD plutôt que windows et pensez être safe: c'est mort

- vous déconnectez vos PC du réseau (filaire, wifi, bluetooth, 3G, etc..) pour empêcher un malware de communiquer: c'est mort

Vous n'y croyez pas?

https://twitter.com/dragosr

http://arstechnica.com/security/2013/10/meet-badbios-the-mysterious-mac-and-pc-malware-that-jumps-airgaps/

http://www.rootwyrm.com/2013/11/the-badbios-analysis-is-wrong/

http://blog.sesse.net/blog/tech/2013-11-02-13-25_badbios_and_ultrasound.html

dimanche 13 octobre 2013

ht editor

Puisqu'il est possible d'ajouter du trailing à un fichier ELF sans qu'il ne se passe rien, je me demande comment faire pour mettre du code dans ce trailing et pointer dessus en modifiant l'entrypoint. Ca devrait être simple, mais je trouve pas vraiment de manière de faire.

Ce dont j'ai besoin:

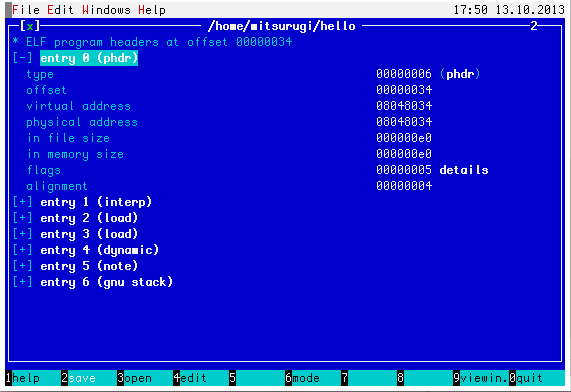

Si je regarde les program headers par exemple (F6 puis program headers):

L'entry0 est le physical header. Il débute à 0x08048034, offset 0x34 soit 52. Cela rejoint donc ce qui dit la commande readelf:

$ readelf -e hello | grep program

Start of program headers: 52 (bytes into file)

et nous pouvons trouver les suivants, et le mapping entre le fichier sur disque et le fichier en mémoire, il s'agit apparemment d'une conversion simple offset --> 0x08048000+offset.

Vérifions à l'aide d'objdump -d:

080482d0 <_start>:

80482d0: 31 ed xor %ebp,%ebp

80482d2: 5e pop %esi

80482d3: 89 e1 mov %esp,%ecx

80482d5: 83 e4 f0 and $0xfffffff0,%esp

80482d8: 50 push %eax

80482d9: 54 push %esp

80482da: 52 push %edx

80482db: 68 30 84 04 08 push $0x8048430

80482e0: 68 d0 83 04 08 push $0x80483d0

80482e5: 51 push %ecx

80482e6: 56 push %esi

80482e7: 68 84 83 04 08 push $0x8048384

80482ec: e8 b3 ff ff ff call 80482a4 <__libc_start_main@plt>

80482f1: f4 hlt

80482f2: 90 nop

Et dans le binaire, si je regarde à x02d0 jusqu'à 0x2f2

$ dd if=hello of=_start bs=1 count=35 skip=720

35+0 enregistrements lus

35+0 enregistrements écrits

35 octets (35 B) copiés, 0,00425817 s, 8,2 kB/s

$ hexdump -C _start

00000000 31 ed 5e 89 e1 83 e4 f0 50 54 52 68 30 84 04 08 |1í^.á.äðPTRh0...|

00000010 68 d0 83 04 08 51 56 68 84 83 04 08 e8 b3 ff ff |hÐ...QVh....è³ÿÿ|

00000020 ff f4 90 |ÿô.|On retrouve le code.

Prochaines étapes:

Ce dont j'ai besoin:

- savoir comment le fichier du disque se retrouve en mémoire

- savoir comment ajouter le trailing du fichier dans la mémoire

- modifier l'entry point (ça c'est le + simple) ou modifier n'importe quel appel de fonction pour pointer sur mon code ajouté

Si je regarde les program headers par exemple (F6 puis program headers):

L'entry0 est le physical header. Il débute à 0x08048034, offset 0x34 soit 52. Cela rejoint donc ce qui dit la commande readelf:

$ readelf -e hello | grep program

Start of program headers: 52 (bytes into file)

et nous pouvons trouver les suivants, et le mapping entre le fichier sur disque et le fichier en mémoire, il s'agit apparemment d'une conversion simple offset --> 0x08048000+offset.

Vérifions à l'aide d'objdump -d:

080482d0 <_start>:

80482d0: 31 ed xor %ebp,%ebp

80482d2: 5e pop %esi

80482d3: 89 e1 mov %esp,%ecx

80482d5: 83 e4 f0 and $0xfffffff0,%esp

80482d8: 50 push %eax

80482d9: 54 push %esp

80482da: 52 push %edx

80482db: 68 30 84 04 08 push $0x8048430

80482e0: 68 d0 83 04 08 push $0x80483d0

80482e5: 51 push %ecx

80482e6: 56 push %esi

80482e7: 68 84 83 04 08 push $0x8048384

80482ec: e8 b3 ff ff ff call 80482a4 <__libc_start_main@plt>

80482f1: f4 hlt

80482f2: 90 nop

Et dans le binaire, si je regarde à x02d0 jusqu'à 0x2f2

$ dd if=hello of=_start bs=1 count=35 skip=720

35+0 enregistrements lus

35+0 enregistrements écrits

35 octets (35 B) copiés, 0,00425817 s, 8,2 kB/s

$ hexdump -C _start

00000000 31 ed 5e 89 e1 83 e4 f0 50 54 52 68 30 84 04 08 |1í^.á.äðPTRh0...|

00000010 68 d0 83 04 08 51 56 68 84 83 04 08 e8 b3 ff ff |hÐ...QVh....è³ÿÿ|

00000020 ff f4 90 |ÿô.|On retrouve le code.

Prochaines étapes:

- vérifier ou se retrouve le trailer dans la mémoire

- trouver dans les headers les tailles des différents objets, headers, programmes, etc..

Mitsurugi

lundi 7 octobre 2013

ajout de code à un binaire elf?

Si je reprends mon hello world:

./hello

Hello World

Je peux ajouter plein de garbage à la fin:

$ hexdump -C nops

00000000 90 90 90 90 90 90 90 90 90 90 90 90 90 90 90 90 |................|

*

000000fb

$ cat hello nops > big

$ chmod +x big

$ ./big

Hello World

$

La question que je me pose, c'est comment charger tous ces nops en mémoire, puis de faire pointer l'EntryPoint dessus.

La fin du binaire n'est pas une zone de code, cela voudrait dire que je devrais tweaker les sections pour en ajouter une? N'y a t'il pas plus simple?

./hello

Hello World

Je peux ajouter plein de garbage à la fin:

$ hexdump -C nops

00000000 90 90 90 90 90 90 90 90 90 90 90 90 90 90 90 90 |................|

*

000000fb

$ cat hello nops > big

$ chmod +x big

$ ./big

Hello World

$

La question que je me pose, c'est comment charger tous ces nops en mémoire, puis de faire pointer l'EntryPoint dessus.

La fin du binaire n'est pas une zone de code, cela voudrait dire que je devrais tweaker les sections pour en ajouter une? N'y a t'il pas plus simple?

Mitsurugi

samedi 5 octobre 2013

Changement de l'entry point

Un peu de code:

$ cat hello.c

#include <stdio.h>

int fonction(void)

{

printf("Je suis dans la fonction\n");

return 0;

}

int main(void)

{

printf("Je suis dans le main\n");

return 0;

}

Un binaire ELF démarre par son entry point:

$ readelf -h hello | grep Entry

Entry point address: 0x80482d0

Si je change l'entry point par l'adresse de fonction, j'affiche "Je suis dans la fonction".

$ objdump -d hello | grep fonction

08048384 <fonction>:

$ hexdump -C hello | head -4

00000000 7f 45 4c 46 01 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |.ELF............|

00000010 02 00 03 00 01 00 00 00 84 83 04 08 34 00 00 00 |............4...|

00000020 fc 09 00 00 00 00 00 00 34 00 20 00 07 00 28 00 |ü.......4. ...(.|

00000030 23 00 20 00 06 00 00 00 34 00 00 00 34 80 04 08 |#. .....4...4...|

Et donc:

$ ./hello

Je suis dans la fonction

Erreur de segmentation

Ca marche, mais ça plante.

En fait, l'entry point ne démarre pas dans main, mais dans une fonction _start qui doit faire des trucs. D'ailleurs, avec objdump, on voit qu'il se passe des trucs:

080482d0 <_start>:

80482d0: 31 ed xor %ebp,%ebp

80482d2: 5e pop %esi

80482d3: 89 e1 mov %esp,%ecx

80482d5: 83 e4 f0 and $0xfffffff0,%esp

80482d8: 50 push %eax

80482d9: 54 push %esp

80482da: 52 push %edx

80482db: 68 30 84 04 08 push $0x8048430

80482e0: 68 d0 83 04 08 push $0x80483d0

80482e5: 51 push %ecx

80482e6: 56 push %esi

80482e7: 68 a1 83 04 08 push $0x80483a1

80482ec: e8 b3 ff ff ff call 80482a4 <__libc_start_main@plt>

L'adresse de main est à 0x80483a1. Je pense que si je modifie le binaire à cet endroit pour y mettre l'adresse de fonction, tout se passera mieux:

000002E0 68 D0 83 04 08 51 56 68 84 83 04 08 E8 B3 FF FF h....QVh........Et:

$ ./hello

Je suis dans la fonction

$

$ cat hello.c

#include <stdio.h>

int fonction(void)

{

printf("Je suis dans la fonction\n");

return 0;

}

int main(void)

{

printf("Je suis dans le main\n");

return 0;

}

Un binaire ELF démarre par son entry point:

$ readelf -h hello | grep Entry

Entry point address: 0x80482d0

Si je change l'entry point par l'adresse de fonction, j'affiche "Je suis dans la fonction".

$ objdump -d hello | grep fonction

08048384 <fonction>:

$ hexdump -C hello | head -4

00000000 7f 45 4c 46 01 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |.ELF............|

00000010 02 00 03 00 01 00 00 00 84 83 04 08 34 00 00 00 |............4...|

00000020 fc 09 00 00 00 00 00 00 34 00 20 00 07 00 28 00 |ü.......4. ...(.|

00000030 23 00 20 00 06 00 00 00 34 00 00 00 34 80 04 08 |#. .....4...4...|

Et donc:

$ ./hello

Je suis dans la fonction

Erreur de segmentation

Ca marche, mais ça plante.

En fait, l'entry point ne démarre pas dans main, mais dans une fonction _start qui doit faire des trucs. D'ailleurs, avec objdump, on voit qu'il se passe des trucs:

080482d0 <_start>:

80482d0: 31 ed xor %ebp,%ebp

80482d2: 5e pop %esi

80482d3: 89 e1 mov %esp,%ecx

80482d5: 83 e4 f0 and $0xfffffff0,%esp

80482d8: 50 push %eax

80482d9: 54 push %esp

80482da: 52 push %edx

80482db: 68 30 84 04 08 push $0x8048430

80482e0: 68 d0 83 04 08 push $0x80483d0

80482e5: 51 push %ecx

80482e6: 56 push %esi

80482e7: 68 a1 83 04 08 push $0x80483a1

80482ec: e8 b3 ff ff ff call 80482a4 <__libc_start_main@plt>

L'adresse de main est à 0x80483a1. Je pense que si je modifie le binaire à cet endroit pour y mettre l'adresse de fonction, tout se passera mieux:

000002E0 68 D0 83 04 08 51 56 68 84 83 04 08 E8 B3 FF FF h....QVh........Et:

$ ./hello

Je suis dans la fonction

$

Mitsurugi

vendredi 4 octobre 2013

En tête ELF

Les fichiers exécutables sous linux sont format ELF. Le format est décrit sur wikipedia (ELF). Par exemple, le 5e octet définit l'architecture du binaire. Si cet octet vaut 1, c'est du 32 bits, s'il vaut 2, c'est du 64 bits. L'archi est défini au 19e octet. Jouons un peu avec un hello world:

$ cat hello.c

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

printf("Hello World\n");

return 0;

}

$ make hello

cc hello.c -o hello

$ hexdump -C hello | head -2

00000000 7f 45 4c 46 01 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |.ELF............|

00000010 02 00 03 00 01 00 00 00 20 83 04 08 34 00 00 00 |........ ...4...|$ file hello

hello: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, Intel 80386, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked (uses shared libs), for GNU/Linux 2.6.26, BuildID[sha1]=0x0b170e8da236317529906c11be894759a87a8cc3, not stripped

$

On peut "transformer" ce binaire en 64bits avec un coup de hexedit:

$ hexdump -C hello | head -2

00000000 7f 45 4c 46 02 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |.ELF............|

00000010 02 00 3e 00 01 00 00 00 20 83 04 08 34 00 00 00 |..>..... ...4...|

$ file hello

hello: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), corrupted program header size, corrupted section header size

Et voilà, un beau binaire 64 bits :)

File râle un peu car le 64 bit va chercher ailleurs les infos de taille de programme et de header. On peut les calculer d'ailleurs.

En vert le 32 bit pour le start of program headers et section headers. En souligné pour le 64 bit. (Il faut décaler de 4 octets car il y a l'entry point sur 64 bits avant)

$ hexdump -C hello | head -4

00000000 7f 45 4c 46 02 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |.ELF............|

00000010 02 00 3e 00 01 00 00 00 20 83 04 08 34 00 00 00 |..>..... ...4...|

00000020 a8 07 00 00 00 00 00 00 34 00 20 00 08 00 28 00 |........4. ...(.|

00000030 1f 00 1c 00 06 00 00 00 34 00 00 00 34 80 04 08 |........4...4...|

Ce qui représente une taille de section headers de 0x0028000800200034 soit 11259033430261812 octets (!!). Ca se confirme avec un coup de readelf:

$ readelf -h hello

ELF Header:

Magic: 7f 45 4c 46 02 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

Class: ELF64

Data: 2's complement, little endian

Version: 1 (current)

OS/ABI: UNIX - System V

ABI Version: 0

Type: EXEC (Executable file)

Machine: Intel 80386

Version: 0x1

Entry point address: 0x3408048320

Start of program headers: 1960 (bytes into file)

Start of section headers: 11259033430261812 (bytes into file)

Flags: 0x1c001f

Size of this header: 6 (bytes)

Size of program headers: 0 (bytes)

Number of program headers: 52

Size of section headers: 0 (bytes)

Number of section headers: 32820

Section header string table index: 2052

$

$ cat hello.c

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void) {

printf("Hello World\n");

return 0;

}

$ make hello

cc hello.c -o hello

$ hexdump -C hello | head -2

00000000 7f 45 4c 46 01 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |.ELF............|

00000010 02 00 03 00 01 00 00 00 20 83 04 08 34 00 00 00 |........ ...4...|$ file hello

hello: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, Intel 80386, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked (uses shared libs), for GNU/Linux 2.6.26, BuildID[sha1]=0x0b170e8da236317529906c11be894759a87a8cc3, not stripped

$

On peut "transformer" ce binaire en 64bits avec un coup de hexedit:

$ hexdump -C hello | head -2

00000000 7f 45 4c 46 02 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |.ELF............|

00000010 02 00 3e 00 01 00 00 00 20 83 04 08 34 00 00 00 |..>..... ...4...|

$ file hello

hello: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), corrupted program header size, corrupted section header size

Et voilà, un beau binaire 64 bits :)

File râle un peu car le 64 bit va chercher ailleurs les infos de taille de programme et de header. On peut les calculer d'ailleurs.

En vert le 32 bit pour le start of program headers et section headers. En souligné pour le 64 bit. (Il faut décaler de 4 octets car il y a l'entry point sur 64 bits avant)

$ hexdump -C hello | head -4

00000000 7f 45 4c 46 02 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |.ELF............|

00000010 02 00 3e 00 01 00 00 00 20 83 04 08 34 00 00 00 |..>..... ...4...|

00000020 a8 07 00 00 00 00 00 00 34 00 20 00 08 00 28 00 |........4. ...(.|

00000030 1f 00 1c 00 06 00 00 00 34 00 00 00 34 80 04 08 |........4...4...|

Ce qui représente une taille de section headers de 0x0028000800200034 soit 11259033430261812 octets (!!). Ca se confirme avec un coup de readelf:

$ readelf -h hello

ELF Header:

Magic: 7f 45 4c 46 02 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

Class: ELF64

Data: 2's complement, little endian

Version: 1 (current)

OS/ABI: UNIX - System V

ABI Version: 0

Type: EXEC (Executable file)

Machine: Intel 80386

Version: 0x1

Entry point address: 0x3408048320

Start of program headers: 1960 (bytes into file)

Start of section headers: 11259033430261812 (bytes into file)

Flags: 0x1c001f

Size of this header: 6 (bytes)

Size of program headers: 0 (bytes)

Number of program headers: 52

Size of section headers: 0 (bytes)

Number of section headers: 32820

Section header string table index: 2052

$

Mitsurugi

jeudi 3 octobre 2013

lavabit et sa clé SSL

On lit dans l'article http://www.wired.com/threatlevel/2013/10/lavabit_unsealed/ que lavabit a été fermé car la NSA voulait les clés privées utilisées par le service.

On se doutait bien que la NSA était derrière, avec les mails (et tous leurs metadata associés) de snowden en ligne de mire. Mais je lis au milieu de l'article:

On se doutait bien que la NSA était derrière, avec les mails (et tous leurs metadata associés) de snowden en ligne de mire. Mais je lis au milieu de l'article:

With the SSL keys, and a wiretap, the FBI could have decrypted all web sessions between Lavabit users and the site, (...).Et là, je dis WTF?! Lavabit n'utilisait le perfect forward secrecy? Ils s'appelaient service de sécu?

Mitsurugi

mercredi 2 octobre 2013

un crackme

Certains crackmes simples peuvent se résoudre très rapidement.

J'en prends un sur crackmes.de (je change juste le nom). On constate:

$ ls -l crackme

-rw-r--r-- 1 mitsurugi mitsurugi 612 oct. 2 17:05 crackme

$ strings crackme

Password :

Great you did it !:)

QTBXCTU

$ ./crackme

Password : QTBXCTU

$

Ok, donc le mot de passe est obfusqué. Sans se poser de questions, on se dit que le mot de passe est peut-être simplement X-oré vu la taille du programme:

$ objdump -d crackme | grep xor

80480b3: 31 db xor %ebx,%ebx

80480b7: 34 21 xor $0x21,%al

OK, 0x21 semble le bon candidat; une console ipython donne le résultat immédiatement:

$ ipython

In [1]: v = ''

In [2]: for p in 'QTBXCTU':

...: v += chr((ord(p)^0x21))

...:

In [3]: print v

pucybut

$ ./crackme

Password : pucybut

Great you did it !:)

Inutile d'essayer de reverser le reste.

J'en prends un sur crackmes.de (je change juste le nom). On constate:

$ ls -l crackme

-rw-r--r-- 1 mitsurugi mitsurugi 612 oct. 2 17:05 crackme

$ strings crackme

Password :

Great you did it !:)

QTBXCTU

$ ./crackme

Password : QTBXCTU

$

Ok, donc le mot de passe est obfusqué. Sans se poser de questions, on se dit que le mot de passe est peut-être simplement X-oré vu la taille du programme:

$ objdump -d crackme | grep xor

80480b3: 31 db xor %ebx,%ebx

80480b7: 34 21 xor $0x21,%al

OK, 0x21 semble le bon candidat; une console ipython donne le résultat immédiatement:

$ ipython

In [1]: v = ''

In [2]: for p in 'QTBXCTU':

...: v += chr((ord(p)^0x21))

...:

In [3]: print v

pucybut

$ ./crackme

Password : pucybut

Great you did it !:)

Inutile d'essayer de reverser le reste.

Mitsurugi

lundi 30 septembre 2013

du code

Premier article pour tester des trucs avec la plateforme blogspot

XOR EAX,EAX

permet de mettre le registre EAX à 0. C'est apparemment plus rapide que de faire un

MOV EAX,0

XOR EAX,EAX

permet de mettre le registre EAX à 0. C'est apparemment plus rapide que de faire un

MOV EAX,0

Inscription à :

Articles (Atom)